Your cart is currently empty!

The Many Failures of Adolphe Sax

Motivational Self-Helpers and Ted-talking business coaches love to talk about personal failure – it lets them extol the virtues of grit and perseverance while selling you the idea that if you keep trying you too can eventually land on the idea which will make your fortunes.

This is a similar story, but with a different moral – even after the successes there can be more failures, and it’s impossible to know where a legacy will lie. It may not be helpfully motivational, but perhaps it could be – either way, this is a story of an inventor who, despite naming nearly all his inventions after himself, is largely forgotten.

Inventing Instruments

Where do musical instruments come from? Audiences like to think of instruments as having emerged fully formed out of the mists of time, or of having evolved slowly from some ancient equivalent into what we use today.

Take, for example, the flute, in which you can trace an evolving lineage from vulture-bone flutes found in ancient caves, through Baroque wooden flutes and into the modern metal flute with its matrix of keys. From there, it’s only a short leap into Jethro Tull and Anchorman Ron Burgundy.

The violin, which – while outwardly the same for the last half-millenium – has subtly changed technologically, to the extent that a modern player struggles to play an original 400 year old instrument (and vice versa should a modern one be sent back in time). However it has remained largely stable since the late 19th Century with only incremental advances in manufacturing method and construction.

The piano, which rather than being one instrument is a series of invented components that were compiled into one instrument by a variety of different inventors and makers over the centuries, from keyboard and pedal mechanisms drawn from clockwork and cabinetmaking methods to iron mineralogy and wood seasoning and laminating technologies. The piano is still being developed today using computer aided design methods and modern engineering production workflows.

Because of these charismatic examples, we feel that musical instruments develop and evolve on their own, without the impact of makers. We’re so used to thinking of instruments as alive, and many of the original makers are lost to history: We don’t know who first thought of putting a bridge on a violin or who first came up with the trombone bell, and so we assume that all instruments have that same nebulous quality – they just exist and they’re just there.

Psychologically we are used to looking at our technologically advanced 21st century lives, and comparing them to the candlelight-and-carpentry image of the past, and assuming that these artisans were not working at the cutting edge of innovation, engineering, and technology.

Many of what we now think of as ‘ancient’ instruments were actually invented by talented individuals – and sometimes we know the identity of those individuals. Some of these inventors were one hit wonders who specialised in their instrument for their entire career, some of them extraordinarily prolific either as instrument inventors or in other fields.

Eponymous Inventors

Inventors of significant musical instruments include Benjamin Franklin, noted American politician, scientist and inventor of the glass harmonica (also called the glass harp). This was a series of spinning glass bowls stacked along a spinning axis (like a fragile doner kebab) that you play with wetted fingers like wine glasses: it swept high-society Europe in the 18th century and gained such a notoriety that it was believed to drive either the player or the listener insane.

Towards the end of the 19th century, we have Auguste Victor Mustel and his organ factory in Paris where he came up with the first keyed Celeste. Tchaikovsky visited his workshop and was so enamoured he purchased two celestes to take back to Russia, subsequently writing the dance of the Sugar Palm fairy for one of those instruments and forever associating it with Christmas and Magic.

In more modern terms we think of Leon Theremin, inventor of the Theremin, who was also a radio engineer who worked for the Russian secret services, notably bugging the US embassy in Moscow and experimenting with contactless radio communications and interference. The instrument he accidentally invented in this process became successful as a very early electronic instrument, and was exported as part of the Soviet propaganda effort.

In the West we had Robert Moog, the inventor of the Moog synth which revolutionised and popularised electronic music thanks to rapid adoption by performers and successful commercial releases such as Switched On Bach and established so many elements in the modern world of synths.

However, the most prolific and (in some ways) successful instrument inventor and manufacturer in modern history was a Belgian boy-genius named Adolphe Sax.

The Failures of Adolphe Sax

Adolphe Sax knew from an early age that he was going to invent musical instruments.

He was born in Belgium to a family of woodwind makers, his father was a wood carver and a self taught instrument maker who ended up as woodwind maker to the Belgian royal court and military bands, and their hometown Dinant had been making objects from shiny yellow brass plate since the mediaeval era. His mother was also a skilled maker in the family business and from a very early age, Adolphe assisted them in the workshop. By his early teens he had started making his first flutes and clarinets and was starting to invent improvements and refinement to these woodwind instruments.

For someone who was so clearly determined to make instruments and to take over the world with his inventions, he was remarkably close to catastrophe throughout his entire life. He nearly died at least seven times during his childhood in incredibly silly ways, including accidentally drinking poison, falling off a three storey building, and swallowing a pin. But he was fine. He survived. He kept on making instruments.

After school he went to the Royal Conservatory of Brussels where he studied flute and clarinet performance, alongside some voice and composition, and then returned to the family workshops, making some improvements to the bass clarinet and manufacturing ophicleides. At age 28 he relocated his workshop to Paris, setting up to manufacture and sell his own instruments.

The fact that he was trained as a musician as well as an instrument maker was important for his success. For example, when he improved the bass clarinet and presented his new version of the instrument to the world, he proved its merit through suggesting a musical duel against the most preeminent bass clarinettist in Brussels at the time: the celebrity Belgian bass clarinettist used his own older instrument and the audience were wowed by Adolphe Sax’s increased low range, versatility, and purity of tone.

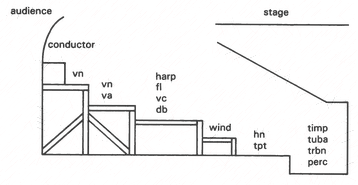

After moving to Paris, he also became offstage conductor and director of the Paris Opera banda (offstage band). While there, he worked with major composers of the time on their new operas, and pushed his own instruments for use as offstage band instruments. As there was no standard offstage band ensemble (in the way that there was in the orchestra pit) he was often able to suggest to these composers that they use this thing he invented as a basis for an ensemble offstage … or even onstage.

In addition to his work in the opera, he got contracts with the French army to supply them with all of their marching band instruments, and won prizes for invention and instrument manufacture. He was incredibly inventive and kept going back to these expositions with new instruments and entering competitions as a maker, much to the consternation of other more established and old school makers. It’s rumoured that one of them kicked his entry off the stage platform while Sax wasn’t in the room, so that he couldn’t win. But Sax also had three other instruments that he’d also made entered at that competition and still did very well.

His greatest success, however, is the saxophone. We have heard of it, but in his time, it wasn’t a success. And despite his prolificacy, most of his inventions were not commerically successful or musically useful. Peppered in there, however, were great successes: instruments we are still using today, with technical improvements ahead of their time.

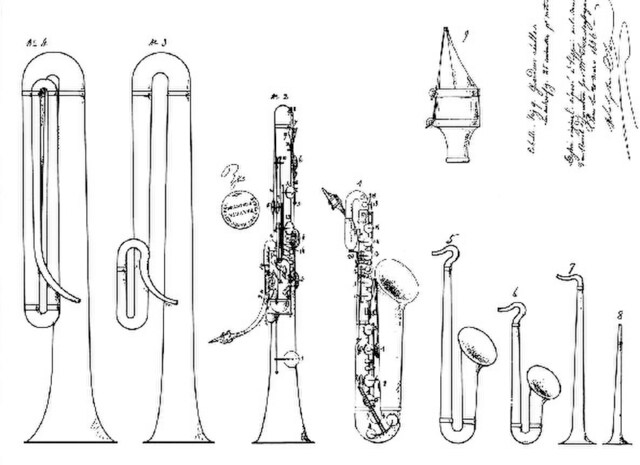

Saxhorns

His first major endeavour after entering the world of professional instrument invention, and his first success as a maker, was a set of valved bugles to be used as marching instruments that he named the Saxhorns. Their name is mostly forgotten now but the family of instruments still exists and included the Flugelhorn and the Euphonium and are popular today as British Brass Band instruments, in American marching bands, and as parents of the modern orchestral brass section. His piston valve mechanism was cutting edge at the time and has remained largely unchanged. This was an entire family of instruments ranging from small cornets down to low euphoniums covering the entire range of the section so that they could all be played together and sold in bulk and played in bulk.

Saxotromba.

After the success of the saxhorn, he made the Saxotromba. It was a narrower bore valve instrument, made of brass, that had a low register and a brighter sound than the saxhorns. The ‘bore’ in a wind instrument is the inside diameter of the tube that the air passes through: trumpets have a cylindrical bore (staying the same width the entire length of the instrument before opening into a relatively small bell), horns and bugles have a conical bore. The Saxotromba was halfway between the two.

Clarinette-bourdon

This was an unsuccessful early attempt to to contra-bass clarinet (the size below the bass clarinet)

Saxophone

This is a brass conical single-reed instrument, unlike any of the other inventions so far, technically similar to a clarinet but made out of shiny yellow brass. This was a measured success: he was defending his patent in the French courts for more than 20 years, pushed for a new course at the Paris Conservatory, manufactured 1000s of these in his factory and had the support of great composers and conductors such as Berlioz and Massinet.

However, it’s success in his lifetime was limited. It didn’t make its way into the symphony orchestra at the time. It was successful in the army and marching band scene but aside from that the instrument required a lot of attention and work for Sax to keep it in the public eye. It had a rich bright sound with a lot more projection than traditional woodwind instruments, and so was perfectly suited to marching bands and theatre bands but not the orchestral canon.

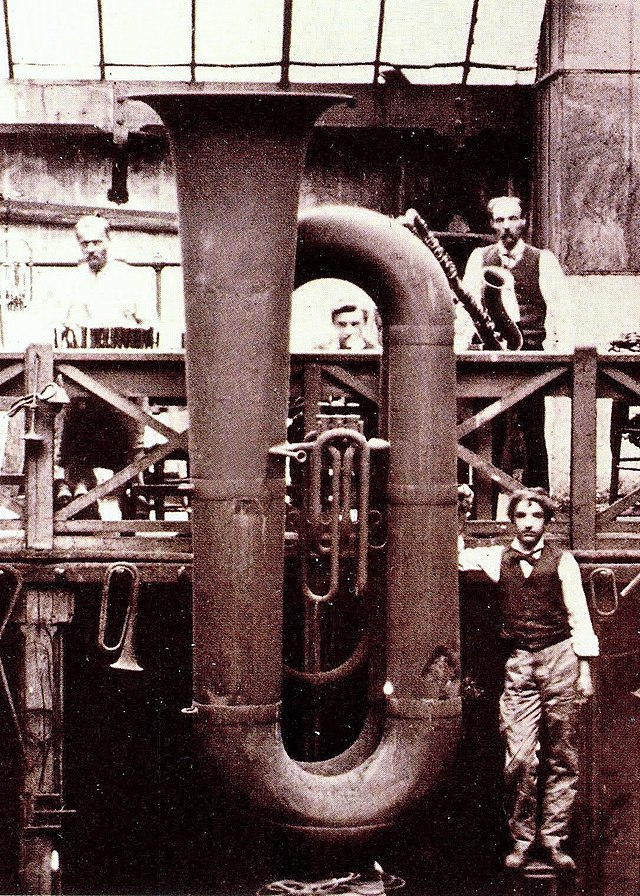

Saxtuba

He followed the success of the saxophone with another failure. An obsolete wraparound absolutely massive tuba, the saxtuba was large and impractical and only used in one opera where Sax happened to be the band director. It was then largely forgotten except for an engraving where a man is absolutely wrapped in heavy metal tubes, unable to sit down.

6-Piston Trombone

He also invented a six-piston trombone, which had valves rather than a slide and required both hands to play. It sits on the floor and goes over your shoulder and was incredibly heavy as you only use one valve at a time for each of its seven notes so every player would need to learn new fingerings and although people remarked that it was very well made, it was very impractical.

7-Bell Trombone

Similarly, there was a trombone with seven bells, one for every note. It was unwieldy, impractical and had a steep learning curve. There are some modern multi-bell trumpets, but the idea never really took off.

Wagner Tuba

It’s worth talking about the Wagner tuba as an honorable invention of Adoph Sax. He didn’t actually make it himself: Wagner toured his workshop in Paris while working on his Ring cycle and liked the saxhorn family of instruments. He went back to Germany and paid a local workshop to pirate it – changing a few things and crossing it with a traditional nordic instrument for its lovely artistic curve. So there is a lineage to Adoph Sax there but it is not strictly a saxophone. It’s not strictly a Sax instrument, but still exists in orchestras and in France is still called the Saxotromba.

So how did Adolphe Sax manage to be so prolific and so successful, despite the initial lack of uptake of his instruments?

It was an incredibly inventive and industrious age, where craftsmen and composers were pushing the scale and experimentation in their work. Into this cultural ferment stepped a highly skilled craftsman but also an accomplished musician, who had a real understanding of both the making and the playing of an instrument.

His big innovations in instrument making were:

- The material is less important than the geometry: Whether you make a flute out of ivory or wood or metal affects the sound less than the fact it has a conical bore and holes in particular positions

- Bending a pipe doesn’t affect the sound passing through it: before his time trumpets largely had single straight tubes, which meant they were incredibly long, particularly when moving into lower registers. He really took advantage of the fact that you can bend a metal tube in any direction you like and it doesn’t affect the sound at all, giving him far more flexibility in playing style and holding position.

- He also made everything in multiple sizes. Almost all of his instruments came as a range (and in a catalogue, unlike the workshop makers of previous generations) where they all had a similar geometric profile and a similar sound that blended nicely together. And so he invented instrument families rather than single instruments.

This idea of a family meant that there was a much more uptake than there would be if he had just invented one Flugelhorn or a single soprano saxophone.

Despite the fact that he put his name on everything and obviously was incredibly aware of ‘branding’, only the saxhorns were really successful in his lifetime, being taken up by the brass banding movement in the UK and the marching bands in the US. He survived for a long time on French military supplier contracts. The saxophone only became big in the 20th century, long after he died. In general, he was known as a scientific maker, with excellent construction and engineering skills, making well-made instruments with good quality control, improved playability and tone quality.

Aside from the occasional whimsical monstrosity, he had a really strong idea of what his instruments could be, and how they would work for composers and musicians. It was crucially important for him that composers picked up his instruments in writing their music, to ensure demand for his instruments and the longevity of the family. He made friends with the pioneering composers in Paris, having Berlioz and Massinet over to his house for soirees and to play music together. Notably, they were opera composers as well, he made a lot of his inroads into the musical establishment by working with opera composers who then later produced concert music. It was after he died that the saxophone started to find its way into the symphony orchestra, appearing in works by Ravel and Shostakovich.

He died age 79 in poverty after a patent-lawsuit-derived bankruptcy: he was given special protection several times by the French Congress – who deemed him an important figure in France and extended his patent protection beyond the normal term – but it’s quite easy to copy his instruments and to develop on his ideas. He was constantly in litigation throughout the latter part of his life, eventually died in poverty and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

He couldn’t know what would become of his legacy and the incredible success of the saxophone, particularly the alto and tenor saxophones, turning up in the dance bands in the 1940s, the cool jazz of Coltrane, the iconic intro to Baker street, and entering the popular imagination through the opening credits of The Simpsons and on stage played by President Bill Clinton.

It really took off as an instrument to the extent that we’ve almost forgotten the instrument that really made him famous during his lifetime. He invented lots of instruments and was constantly refining and improving the playability and tone colour of his instruments as well as the industrial methods by which they were made, and many of them are still made in very similar ways today. And modern repairs can repair those old instruments just as well as they can new ones because of the high quality with which they were made and the demand for good quality instruments by musicians today. He was persistent, and had many failures throughout his life and career, but his dedication to tone colour and playability has ensured that he and his instruments were not forgotten.

In