Your cart is currently empty!

History: The Orchestra Pit

The orchestra ‘pit’ is clearly the major feature of the theatre musician’s career: the musician will spend the entire show in this place, usually in the dark. De rigueur in early theatre, and still found in many opera houses, the orchestra ‘pit’ was simply an area at the front of the stalls at floor level where the orchestra sat. These stalls, and indeed the entire house, were lit from above throughout the performance. Wagner, in the creation of his theatre at Bayreuth, revolutionised the theatre in two ways: he plunged the entire theatre into darkness, and he buried the orchestra pit below and beneath the stage. These conventions quickly spread to dramatic theatres, and by the twentieth century the pit had become a standard theatrical feature. Mark Lubbock, writing in 1957, remarks that “in a Theatre the orchestra should always be hidden”, and cites dramatic reasons: “otherwise the lights and movements of the conductor and players intervening between the audience and the stage prove very distracting. Apart from this, hidden music greatly adds to the illusion.” However, this impact on the dramatic meaning of the work, while vital, means the requirements of the performing musicians are sidelined: the pit is dark, has a “long narrow shape” where cramped musicians are “packed close together”, and is the perfect receptacle for dust and debris rolling off the stage.

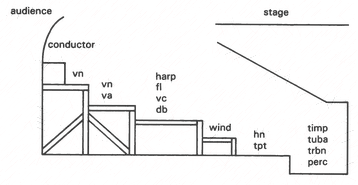

The pit also has unique and potentially problematic acoustic characteristics. The orchestra is playing within a space acoustically designed to bounce sound out of the pit and into the auditorium. A side effect of this internal reflectivity is an environment which presents musicians with a high level of noise. Over time this can cause damage to a musician’s hearing, and performers have to carefully manage their exposure through hearing protection and careful scheduling to minimise decibel exposure. Achieving a proper balance in the sound exiting the pit also presents a challenge to conductors or sound engineers. While technology is able to solve some of these problems now, diagrams of the Wagnerian pit show the strings section on raised platforms near the front, with brass and percussion pushed into the depths as far away from the ‘mystical chasm’ as possible. Consequently the pit is dark, cramped and noisy: hardly the ideal working environment for a musician.

Historically the pit was used primarily for non-diagetic music, such as underscoring and feature pieces, while the ensemble was moved into the ‘picture frame’ of the proscenium arc theatre to enter the world of the narrative. The score for Peer Gynt written by Henrik Grieg provides a good example of this. Along with the conventional pit orchestra he uses backstage choirs and ensembles, onstage performing musicians and singers, and unusual combinations of both onstage and offstage performers.